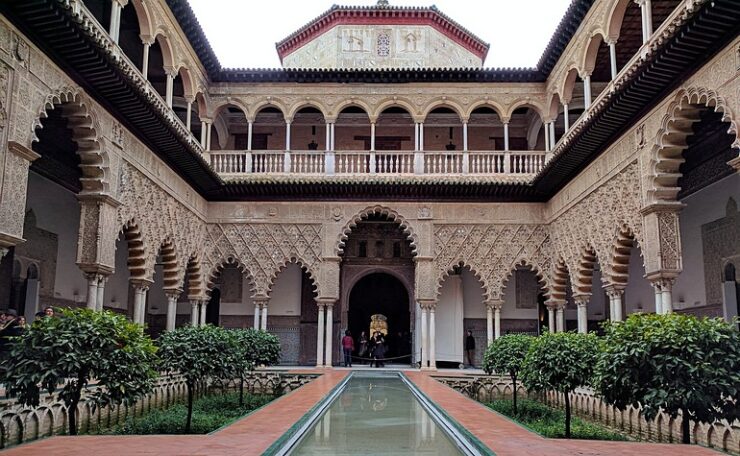

The El Real Alcázar was originally built under the orders of Abd ar-Rahman II in 913 CE as a military fortress on the site of a Visigothic basilica, and later used as a governor’s residence under the Cordoban caliph Abd-ar-Rahman II . The Real Alcázar (then known as Dar al-Imarah) is the oldest palace in Europe still used as a royal residence.

- Sitting directly beside the Cathedral and the Archivo de los Indios, the Alcázar is surprisingly central; with its high curtain walls, crenellations and turrets, from the outside it looks like a medieval fortress taken from the top of a lonely hill and plonked down in the middle of a metropolis.

- The result of a thousand years of successive demolitions and reconstructions according to the taste of the day, it is an extraordinary mishmash of courtyards, rooms and gardens in different styles and from different periods.

- King Pedro the Cruel (who earmt the name for murdering all the half-siblings standing between him and the throne) hired Muslim builders and craftsmen from the Nasrid court of Granada to create the finest examples of Mudéjar art in Spain. These craftsmen apparently without the king even realising, repeatedly carved the Nasrid motto ‘Wa la ghaliba illa Allah’ (‘And none is victor save Allah’) all over the palace complex, adding small crosses to the Arabic, perhaps to disguise the meaning. Elsewhere there are oft-repeated praises of Allah, sometimes coupled with praises to King Pedro.

- The gate to the Dar al-Imarah palace has been bricked up, but visitors can plainly see the original sandstone horseshoe arch, while the turrets of this defensive fortress are visible from the Plaza del Triunfo.

- This leads to the Patio de las Banderas (Courtyard of the Flags), which was originally a parade ground for the city’s troops. This part of the palace features rough walls that date back to the original construction of the nearby Sala de la Justicia (Chamber of Justice). Inscribed on the walls of the Chamber are the Arabic words “Allah is (our) Refuge, Bliss, (and) continual prosperity: Praise be to Allah for His goodness”.

- The Patio de Yeso (Stucco Courtyard) is a beautiful example of Almohad architecture, especially due to the triple arches and sebqa (rhombus mesh) decoration, a style much repeated in other places in Spain and especially in the Alhambra.

- Under the rule of the petty kings, Seville prospered even more than before; these taifa rulers extended the Alcázar and renamed it the Qasr al-Mubarak (the Blessed Palace). However, this was demolished after the Reconquista and replaced by the Archivo de los Indios (House of Trade with the Indies), located nearby, although some parts of it remain.

- The languid poet king Al-Mu’tamid built the sumptuous formal hall known as Al-Thurayya (the Pleiades), which became King Pedro’s Patio de los Embajadores (Hall of the Ambassadors). When Al-Mu’tamid was banished to Aghmat, Morocco, he wrote a poem about his lost palace.

- The Sala de Embajadores is a majestic room, in a shape from Abbasid times, but most of it was created afresh by King Pedro’s workmen. It’s pink columns were reportedly taken from Cordoba’s ruined Madinat Az-Zahrah and its wooden doors are from the 15th century, inscribed in Arabic on one side and Gothic Castilian on the other.

- The adjacent Arco de los Pavones (Arch of the Peacocks) dates from the 1th century and shows the Persian influence in Hispano-Moorish style. An interesting footnote is that parts of the Alhambra imitated this room, only to be imitated again when King Pedro came to remodel the Alcázar in Seville!

- Next to the official area was part of the family area, now called the Patio de las Muñecas (Courtyard of the Dolls). The marble pillars are from Cordoba, and inscribed above an archway is the famous verse of the Throne (Ayat al-Kursi) from the Qur’an. The center floor-based fountain is a customary feature in old Moorish buildings, vital in areas like Seville-located in what is known as the frying pan of Spain, where temperatures easily go up to 47 degrees centigrade or higher in summer.

- The Dormitorio de los Reyes Moros (Bedroom of the Moorish Kings), with its sleeping alcoves that were once hidden by tapestries, offers a peek into the private lives of Muslim royalty living in an 11th century palace. And although they are not open to the public, the rooms used by the Spanish royal family in the Alcázar are of sumptuous Mudéjar decorations, right down to the furniture.

- The style of the Moorish gardens has been greatly changed and is now more Renaissance than Moorish; Renaissance practice was to create gardens that mirrored the interiors. For Muslims, gardens were more important than the houses or palaces they accompanied. They often had sunken orchards, so that one could easily pick oranges from trees without needing a ladder as in the original Patio of Oranges next to the Jamaa (congregational) mosque. They usually had a central feature with four pathways leading to it, and four irrigation channels, to remind the passersby of the four rivers of Paradise. The premise behind all ornamental garden design was to remind one of the heavenly delights to come.

- The Moors were also very practical people, whose dedication to agriculture and botany made huge leaps forward for Spanish livelihoods, so this palace complex originally had two large huertas (vegetable/fruit patches) as well. These were called the Huerta della Alcoba (from the Arabic al-qubba after a beautiful pavilion erected by Felipe I – the Arabic word stuck even after Al-Andalus fell) and Huerta del Retiro, both lying between the palaces and the Tagarete stream.

- As the Alcazar was largely rebuilt under a Christian king during a time when Al-Andalus was already heavily subdued, this is where the newer Northern European styles took centre stage.

- The Real Alcázar’s fabulous gardens include some extraordinary specimens of exotic trees. The Pool Garden (Jardin de Estanque) was the old cistern used for irrigation, and the Almahad wall has been covered with mythological paintings from the 18th and 20th centuries. The Moorish aqueduct can still be seen on a Callejòn del Agua (Water Alley). One of the gardens, Jardin de Troya, still has Moorish lion head fountains. Look out for the late 12th century Almohad Torre de la Alcoba in the wonderful Jardin Ingles, and for the peacocks that scuttle about the lawns quite oblivious to the presence of so many tourists.

- A statue dedicated to King AI-Mu’tamid stands in Jardin de la Galera (the Garden of the Galley) alongside quotes from one of his poems: “Allah grant that I may die in Seville and that our graves be opened there on the Day of) Resurrection”. A poignant memorial for a king whose life after the fall of his beloved city was so impoverished that his wife and daughters had to become seamstresses.

Reference: HUMA’s Travel guide to Islamic Spain