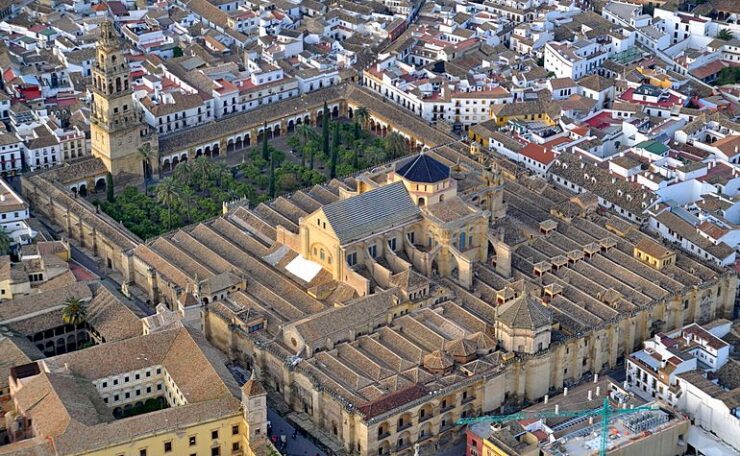

The ‘Mezquita’ (mosque) of Cordoba was originally built on the site of a Roman temple to the god Janus, which had been rebuilt as a church under the Visigoths. Capable of admitting 20,000 worshippers, it was (and remains) one of the largest mosques in the world; following its final extension it now covers 23,400 square metres. Visited by 1.3 million tourists a year, the Mezquita is the only tourist attraction in Spain that dates back to the Muslim period and also houses a functioning cathedral and the offices of the diocese.

- The young Umayyad king Abd al-Rahman I tactfully offered to buy the building (bucking the medieval trend of smashing everything to bits), and separated it into two sections – one side mosque, one side church – in 786 CE. Purchasing the other half not long afterwards in response to the growing Muslim population of Cordoba, he ordered the reconstruction of the building.

- Best known for its infinity of red and white arches, the mosque was constructed with as many as a thousand columns of onyx, jasper, granite and marble, of which 856 now remain. Its emphasis on geometry hints at a connection with North African architecture.

- The main entrance is now the Puerto del Perdón (Gate of Forgiveness) a 14th century Mudéjar arched doorway that opens onto the Patio de los Naranjos (Orange Tree Court). Originally, however, all nineteen rows of columns ended with doors that opened onto the patio, allowing daylight and worshippers to enter freely and continuing the rhythm of the arches.

- Beside the Puerta del Perdón is the 17th century belltower or Alminar, which was built around the original minaret. This structure built of ashlar (cut stone) and reaching 100 cubits or about 46 metres, dated back to about 950 CE and was ascended via two parallel vaulted staircases, accessed from doorways on either side.

- One strange quirk is that the mihrab points not to Mecca but to Ghana, as the homesick Syrian caliph faithfully tried to recreate Damascus in Spain, even in the direction of prayer. Imitating to some extent the Umayyad mosque of Damascus as well as the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, it’s unique style influences other mosques built in Al-Andalus.

- Also built under the orders of Abd al-Rahman I was the oldest existing door to the mosque, the Bab al-Wuzara (Viziers’ Gate), now called the St. Stephen’s Gate (Puerta de San Esteban) on the western side of the mosque.

- Over the course of 200 years, the Mezquita was extended several times with each extension named after the ruler who added to it (Abd al-Rahman I, Abd ar-Rahman II, Al-Hakam II and Al-Mansur) and each reflecting the growth of Cordoba in size and prosperity.

- The entire front wall of the mosque was demolished by Al-Hakam II in order to expand it, and in 961 CE he replaced the previous plain mihrab with an ornate heptagonal niche with a scalloped dome fronted by a low horseshoe arch encrusted with 1600kg of gold mosaic cubes. It is thought that the emperor of Byzantine sent these mosaic tiles, called tesserae, along with an expert mosaicist – who was soon surpassed by the slaves assigned to study under him. The alfiz is delicately carved with arabesques, sculpted marble friezes of geometric patterns and gold Kufic calligraphic inscriptions of Qur’anic passages and references to Al-Hakam II.

- The eastern porch features an arched door (now closed in with a brass door) dating back to the time of Al-Mansur, vizier and de facto ruler of the dying caliphate. This is surrounded by a beautiful alfiz (rectangular surround) composed of three-lobed windows, red and white geometric tile friezes and subtle vegetal designs that echo the designs of Al-Hakam’s mihrab.

- The three bays in front of the mihrab are the Maqsura (Royal Enclosure) where the caliph and his family would pray. Designed to complement the mihrab as a ‘mosque within a mosque’, this area would have been fenced in by a tall carved wooden fence with doors embellished with gold, silver and ebony.

- There are five chambers each to the right and left of the mihrab; those on the eastern side were originally used as a treasury, while those on the western side served as a passage to the palace. Only the central and eastern bays have retained their sumptuous domes, the western one having been destroyed to create the Capilla de Villaviciosa (see below). The aisle leading up to the mihrab was slightly wider than the rest from the beginning: this subtle alteration breaks the monotony of the column spacing and emphasises the mihrab.

- After the fall of Islamic Cordoba, Christian worship was introduced in the building. The Capilla de la Villaviciosa, built in the mid-to-late 13th century, was the first chapel to be used for Christian worship after Reconquista and features a scalloped cupola, corresponding to the Mudéjar period in which Muslim art still held a certain influence even in the construction of Christian buildings – many of the craftsmen were probably Muslims living under Christian rule.

- The biggest alteration, a towering cruciform basilica at the heart of the building in a riot of Renaissance plasterwork, was not built until 1523 CE once the Muslims of Spain had been overthrown. But, not everyone in the new Christian Spain was happy with the changes brought upon the Mezquita-Catedral. Upon seeing the damage done, King Carlos, who had never given the command for the building work to take place, reputedly said, ‘You have destroyed something that was unique to the world.’ Fortunately, the mihrab and the maqsura were largely left untouched. Some commentators have noted that by embedding the cathedral into the mosque it actually preserved the building for future generations, unlike many mosques which were razed completely.

- A recent online petition, interestingly begun by some of Cordoba’s non-Muslim residents, calls for the diocese in charge of running the Mezquita to allow it to be partly used as a Muslim place of worship again and to remove the growing number of statues, shrines and displays that have been added to the stucture of the mosque or accumulated inside the building, hindering views of the mihrab.

- The complex has ceased to be used as a mosque for hundreds of years and anyone attempting to perform the Islamic prayer in the Mezquita-Catedral will be stopped by officials and quickly escorted out of the complex. There is a long-running campaign led by Junta Islamica to allow Muslims to pray here again. The regional government of Andalusia, and particularly its tourist board, are critical of the management of the Mezquita; it generates approximately nine million euros from ticket sales, yet relegates its historic function as a mosque to a secondary role.

Reference: HUMA’s Travel guide to Islamic Spain